Cookbook #182: The Label Reader’s Pocket Dictionary of Food Additives, J. Michael Lapchick, 1993.

Such a long title for such a small booklet! It’s only 4 x 5.5 inches, and indeed could fit into a large pocket. Amazingly, you can still purchase this decades-old book online. From the reviews, it’s a popular little booklet.

I like to know what’s in the foods I eat. I cook from scratch as much as possible – homemade meals including from-scratch baked breads – partly because I can better control what we consume. I often read food labels. In this day and age it’s almost impossible to avoid food industry products (unless you live on a farm). The Pocket Dictionary of Food Additives is a great little reference for deciphering food labels, and the author thinks along the same lines that I do. Here, an excerpt from page 13:

“A certain trust is implied every time we pick a product off the shelf and put it in our grocery carts. We trust the label reads true. We also trust the ingredients are safe, sanitary, and desirable. But as we scan the list of ingredients and they become less and less familiar, we are asked to trust a little more. What about those ingredients we can’t even pronounce? Should we assume the products must be safe if they made it to the supermarket?”

Food additives (chemicals) are added for lots of reasons, for example, to make foods last longer on the shelf, have a better texture, have enhanced nutritive value, and have better flavor and color. Even hundreds of years ago, food additives such as salt were used to make foods last longer, but then, the list of available preserving chemicals was short. This all changed in the mid-twentieth century. According to the Pocket Dictionary of Food Additives, “in the 1900s, particularly after World War II, food manufacturers began to look for ways to market their fresh products nationwide. Products not only had to be fresh, but look and feel fresh, too. The manufacturers turned to chemical companies.”

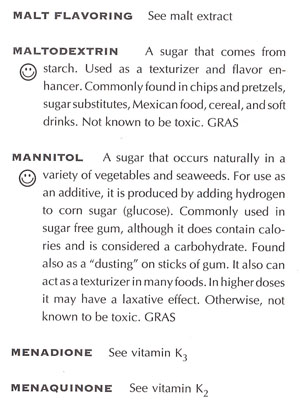

Thus began the flow of chemicals, good and bad, into our food supply. Does the FDA protect us from dangerous food additive chemicals? I turn to page 20 of the Pocket Dictionary of Food Additives, wherein the author states “Today, a new additive first must pass tests required by the FDA. The tests are performed by the chemical manufacturer and evaluated by the FDA. If the results are accepted, the compound is granted a ‘regulated’ status and can be used in food. If the manufacturer wants to pursue a GRAS [Generally Recognized As Safe] rating, which may make it more enticing to food companies, it must publish the test results in certain journals and publications. Still, a GRAS status does not necessarily mean an additive is completely risk-free.” (This last statement is not explained further, but the author does state in earlier pages that several facets of his own health improved when he eliminated food additives from his diet.)

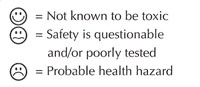

An alphabetical list of food additives makes up the bulk of this book. Each entry includes a smiley-frowny face graphic:

Here is a typical food additive entry:

I can’t cook a recipe from this book (there are none!). But here is an example of something this book would recommend eating, an organic apple! No additives at all.

I will keep this booklet. I admit, though, that I am more likely to search the internet if I am curious about a chemical added to food. Or, I could download an appropriate phone app and have the information at the ready, in my pocket, at the grocery store.

Some thoughts on learning about food additives

My interests in chemistry, and in food, and in healthy eating, probably led me to buy this little book. But I might have purchased it as a reference for my work, when I was the coordinator for the organic chemistry teaching labs at CU Boulder. At the time, I wanted students to become familiar with chemicals they used in their everyday lives. So, I wrote an assignment for beginning organic chemistry lab students that involved reading food and household product labels and learning about the chemicals listed.

We hear so much about what is added to or gets into our foods and our water supplies. Sometimes it’s hard to separate unfounded cries of alarm from scientific fact. For this reason, I often like to go to scientific journal articles and read for myself, employing my research skills in biochemistry/chemistry learned in my long career. Reading a journal article as full text versions gives me an idea of how reliable and accurate the research is.

For instance, this week I came across a lay article entitled “Common Food Additive Promotes Colon Cancer In Mice“. The authors studied two food additives, polysorbate 80 (P80) and carboxymethylcellulose (CMC). Briefly, the researchers concluded that P80 and CMC can alter intestinal bacteria in a manner that promotes intestinal inflammation (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, IBD), which in turn increases the risk of colorectal cancer. According to the Pocket Dictionary of Food Additives, P80 is okay (happy face) and is used as an emulsifier and a stabilizer in salad dressings, baked items, frozen dessert toppings, and pickled items. CMC is not in the booklet; Wikipedia states that it is an emulsifier used in various products such as ice cream.

I read the full text of the journal article:

Dietary emulsifier-induced low-grade inflammation promotes colon carcinogenesis. Emilie Viennois, Didier Merlin, Andrew T. Gewirtz and Benoit Chassaing, Journal of Cancer Research, 7 November 2016.

I first looked to make sure the authors did not have a conflict of interest listed: “none” is stated. This is good. The details of the methods and analyses sound solid to me. The study was done in mice, using doses similar to amounts of the chemicals commonly used in food industry products. My thoughts are that a mouse study might or might not translate to humans. Another question: just because doses used in mice are similar to amounts used in the food industry does not mean that we are actually ingesting these amounts of emulsifiers. All in all, the article convinced me to read the labels of the foods that I cook with and check for P80 and CMC, as well as other emulsifiers. Sounds like eliminating these chemicals from our diet might decrease inflammation in our intestines.