Cookbook #128: Diet for a Small Planet, Frances Moore Lappé, Ballantine Books, NY, NY, 1971.

I bought Diet for a Small Planet in the 1970s when it was a popular book in the health food movement. In this book, Lappé encourages everyone to become vegetarians (or at least eat less meat), because raising meat requires a lot more resources than does growing crops meant for direct human consumption. One drawback to becoming a vegetarian can be a lack of protein in the diet. Lappé has a solution for that: the quality of protein found in meat could be had for vegetarians if they combined specific vegetable groups to obtain “complete proteins”.

I bought Diet for a Small Planet in the 1970s when it was a popular book in the health food movement. In this book, Lappé encourages everyone to become vegetarians (or at least eat less meat), because raising meat requires a lot more resources than does growing crops meant for direct human consumption. One drawback to becoming a vegetarian can be a lack of protein in the diet. Lappé has a solution for that: the quality of protein found in meat could be had for vegetarians if they combined specific vegetable groups to obtain “complete proteins”.

What is a “complete protein”? Here goes. Proteins are made up of chains of amino acids (trust me, this is true, I am a chemist!). According to Lappé, a complete protein contains the eight amino acids that our bodies cannot make: tryptophan, leucine, isoleucine, lysine, valine, threonine, the sulfur containing amino acids, and the aromatic amino acids. These are the essential amino acids, or EAAs. These EAAs must not only be present in our foods, they must be present in the right proportions. And you need to eat the complementary foods in the same meal.

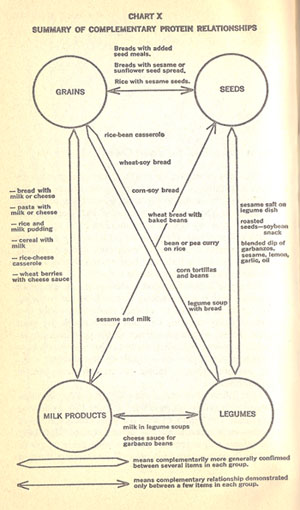

For instance. Nuts like sunflower seeds are high in the amino acid tryptophan and low in lysine, while legumes like black beans are high in the amino acid lysine and low in tryptophan. Toss some sunflower seeds on top of black beans and you consume a complete protein. Examples of other combinations are grains and milk products, seeds and legumes, and grains and legumes. (Note the milk products: this is not a vegan diet.) Often the traditional dishes of cultures exemplify Lappé’s theory: Cajun red beans and rice, India’s dal and flat wheat bread, Mexican beans and corn.

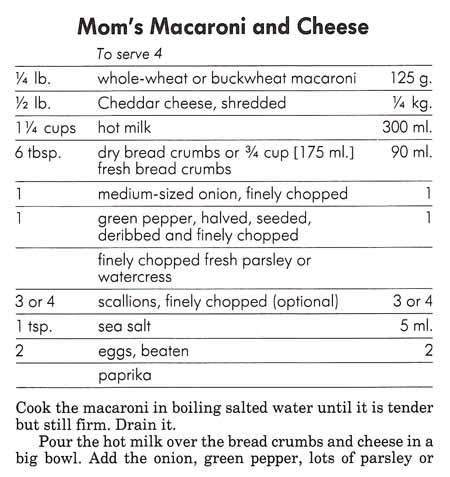

Below is a scan from the book that illustrates the complementary protein scheme:

The first part of Diet for a Small Planet contains a ton of charts and tables to support Lappé’s hypothesis: Amino Acid Content of Foods and Biological Data on Proteins, Food Values of Portions Commonly Used, Composition of Foods, Amino Acid Content of Foods, Protein Requirements, Calorie Cost per Gram of Usable Protein, and more. The data in these tables is supported by bibliographical references. The second half gives recipes for twenty different vegetable combinations.

The first part of Diet for a Small Planet contains a ton of charts and tables to support Lappé’s hypothesis: Amino Acid Content of Foods and Biological Data on Proteins, Food Values of Portions Commonly Used, Composition of Foods, Amino Acid Content of Foods, Protein Requirements, Calorie Cost per Gram of Usable Protein, and more. The data in these tables is supported by bibliographical references. The second half gives recipes for twenty different vegetable combinations.

I swallowed the “complete protein” theory totally, and although I never became a vegetarian, I believed the theory after reading this book. I do remember hearing that you no longer had to eat the combinations in the same meal, only the same day or so. Imagine my surprise when I went online today and found that the complete protein method is no longer held as true!

In this 2013 article, Jeff Novick writes that Lappé’s hypothesis is based on a 1952 article by William Rose that reported minimum daily requirements of the eight EAAs. Rose then doubled the minimum and claimed it as the recommended daily requirement. Novick states: “Modern researchers know that it is virtually impossible to design a calorie-sufficient diet based on unprocessed whole natural plant foods that is deficient in any of the amino acids.” Setting the Record Straight, by Michael Bluejay (2013), is another good article that refutes the complementary protein theory. Interestingly, Wikipedia’s article on Complete Protein does not address the controversy.

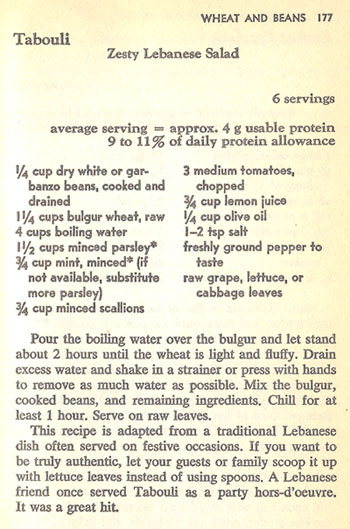

Back to cooking. I decide to make Tabouli, or “Zesty Lebanese Salad”. It incorporates the “complementary protein foods” wheat (bulghur) and legumes (garbanzo beans). Bulghur (or bulgur) is a wheat product, kind of like a cereal. (We enjoyed a related wheat product called burghul or cracked wheat in Turkey. Bulgur is fine-grained and quick-cooking, while burghul takes a long time to cook and is big and chewy.)

Tabouli, or Tabbouleh, is an Arabian dish. It usually doesn’t contain garbanzos (chick peas), although these beans are quite common in Middle Eastern cooking. Lappé’s version of tabouli calls for dried garbanzos and I wanted to use canned ones, so I just sort of guessed at the amount of beans to use. I often make myself a bulghur salad – just tossing ingredients together sans recipe. These facts and my experiences led me to stray from the book’s version of tabouli in my version below.

Tabouli, or Tabbouleh, is an Arabian dish. It usually doesn’t contain garbanzos (chick peas), although these beans are quite common in Middle Eastern cooking. Lappé’s version of tabouli calls for dried garbanzos and I wanted to use canned ones, so I just sort of guessed at the amount of beans to use. I often make myself a bulghur salad – just tossing ingredients together sans recipe. These facts and my experiences led me to stray from the book’s version of tabouli in my version below.

- 1/2 cup bulgur wheat, uncooked

- 1 1/4 cups water

- 1 can garbanzo beans

- 1/2 cup chopped parsley (or to taste)

- 1/4 cup chopped fresh mint (no substitutes!)

- 1/2 cup chopped green onions

- 1 tomato, chopped

- juice of 1 lemon

- 2-4 tablespoons olive oil

- 1/2 teaspoon salt, or to taste

- freshly ground pepper

Boil the water in a pan, then add the bulgur. Leave it on the burner for a minute or two, then remove from the heat and let stand at least 10 minutes. Put in a strainer to drain off all the water, then put it in a bowl.

Add all of the remaining ingredients and mix. Refrigerate until cold. Taste the salad and adjust the seasonings if you want to. Serve as a side dish or over greens.

I really liked this salad, especially with some feta cheese mixed in. And the cookbook, Diet for a Small Planet? I will keep it, for nostalgia rather than the recipes.

I really liked this salad, especially with some feta cheese mixed in. And the cookbook, Diet for a Small Planet? I will keep it, for nostalgia rather than the recipes.

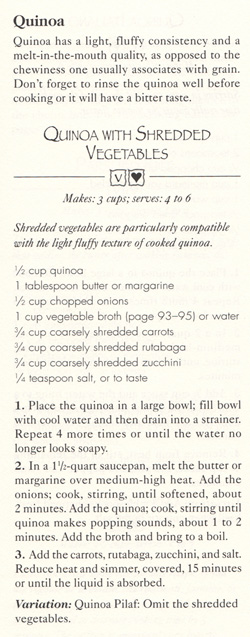

I made it just like the recipe. I used vegetable broth, but I didn’t have any fresh or boxed on hand, so I dissolved a vegetable bouillon cube in a cup of water. This brought a lot of flavor to the dish, so I don’t suggest using just water. And do use a rutabaga, it added a subtle, earthy flavor. I liked it more than my dinner partner, but since I served it with

I made it just like the recipe. I used vegetable broth, but I didn’t have any fresh or boxed on hand, so I dissolved a vegetable bouillon cube in a cup of water. This brought a lot of flavor to the dish, so I don’t suggest using just water. And do use a rutabaga, it added a subtle, earthy flavor. I liked it more than my dinner partner, but since I served it with  And here is the completed dish:

And here is the completed dish: I liked this, and will make it again!

I liked this, and will make it again!