Cookbook #219: Pastries and Desserts, California Home Economics Association, Press of Clyde Browne, Los Angeles, Cal., 1921.

This might have belonged to my maternal grandmother. There is very little handwriting in it, but what there is looks like hers. Or it might have come from Ruth Vandenhoudt, since it is from the same cookbook series as Salads, Vegetables and the Market Basket. There are a few food and age stains, but it is actually in pretty good condition for being 96 years old! I have two copies, and one is missing the cover.

This might have belonged to my maternal grandmother. There is very little handwriting in it, but what there is looks like hers. Or it might have come from Ruth Vandenhoudt, since it is from the same cookbook series as Salads, Vegetables and the Market Basket. There are a few food and age stains, but it is actually in pretty good condition for being 96 years old! I have two copies, and one is missing the cover.

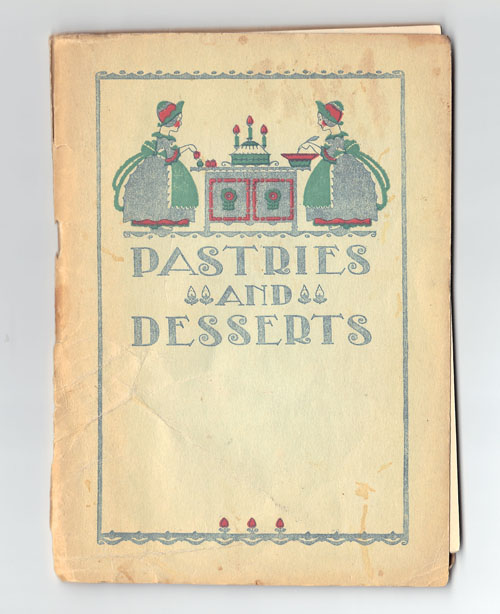

I like the design of the cover and the introductory pages. Here is a scan of the cover, since it gives more detail than my photo:

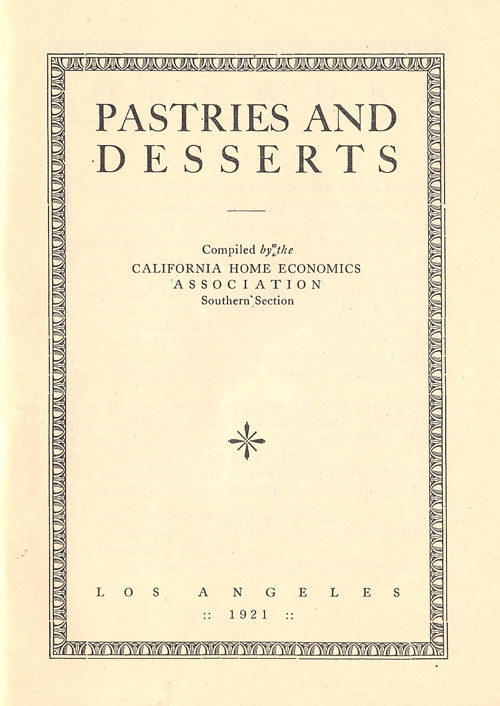

The title page:

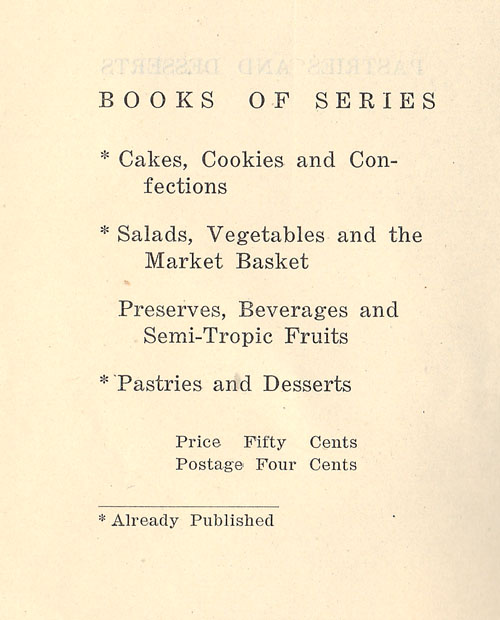

This page is opposite the title page (above) and lists books in the series. I like this: “Price: Fifty Cents. Postage: Four Cents.”

The entire content has a pleasing typeface and layout, no typos, is well-organized with cross-references, and has a very useful index at the end. The content is by the California Home Economics Association, Southern Section, but who is responsible for the printing of this 1921 cookbook? I find “Press of Clyde Browne” and “Cover Design by Stanley Edwards” on the back cover:

The entire content has a pleasing typeface and layout, no typos, is well-organized with cross-references, and has a very useful index at the end. The content is by the California Home Economics Association, Southern Section, but who is responsible for the printing of this 1921 cookbook? I find “Press of Clyde Browne” and “Cover Design by Stanley Edwards” on the back cover:

Clyde Browne, was a self-identified printer, according to a 2014 article in KCETLink. From the KCETLink web site: “. . . Southern California bohemians, whose ideals and aesthetics were inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement, valuing craftsmanship, beauty, nature, and community. Settling along the Arroyo Seco, between Pasadena and Highland Park, these inhabitants created what Kevin Starr calls the ‘Arroyoan ideal: the spiritualization of daily life through an aestheticism tied to crafts and local materials,’ that is ‘expressed primarily through the home.'” Clyde Browne also has a Wikipedia entry.

Clyde Browne, was a self-identified printer, according to a 2014 article in KCETLink. From the KCETLink web site: “. . . Southern California bohemians, whose ideals and aesthetics were inspired by the Arts and Crafts movement, valuing craftsmanship, beauty, nature, and community. Settling along the Arroyo Seco, between Pasadena and Highland Park, these inhabitants created what Kevin Starr calls the ‘Arroyoan ideal: the spiritualization of daily life through an aestheticism tied to crafts and local materials,’ that is ‘expressed primarily through the home.'” Clyde Browne also has a Wikipedia entry.

Sounds like Clyde was a Bohemian, a beatnik, a hippie, a New Age person. Someone who would be right at home in Boulder, Colorado.

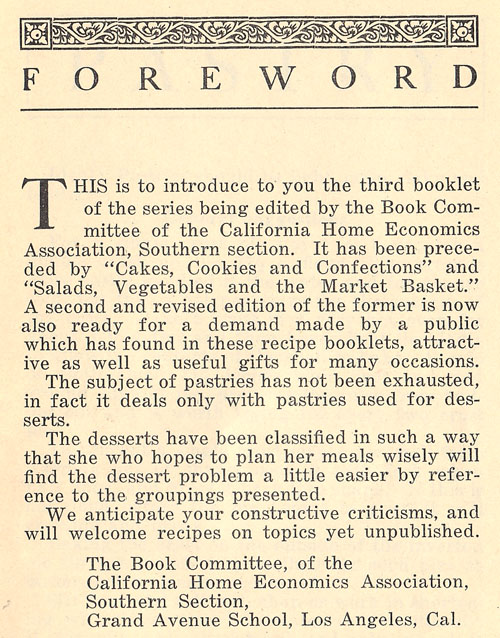

I continue paging through Pastries and Desserts. Here is the foreword:

This foreword tells us that the California Home Economics Association promoted these recipe booklets as “useful gifts for many occasions”. Furthermore, it tells us about the role of women in society in the early twentieth century: “The desserts have been classified in such a way that she who hopes to plan her meals wisely will find the dessert problem a little easier”. (Dessert problem, right.)

This foreword tells us that the California Home Economics Association promoted these recipe booklets as “useful gifts for many occasions”. Furthermore, it tells us about the role of women in society in the early twentieth century: “The desserts have been classified in such a way that she who hopes to plan her meals wisely will find the dessert problem a little easier”. (Dessert problem, right.)

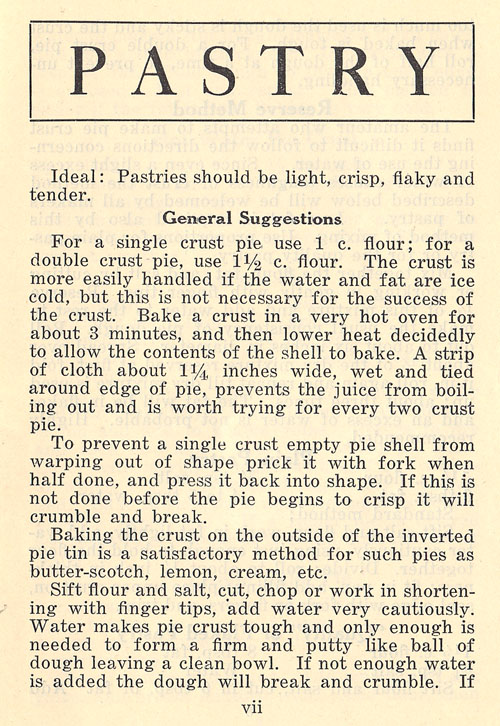

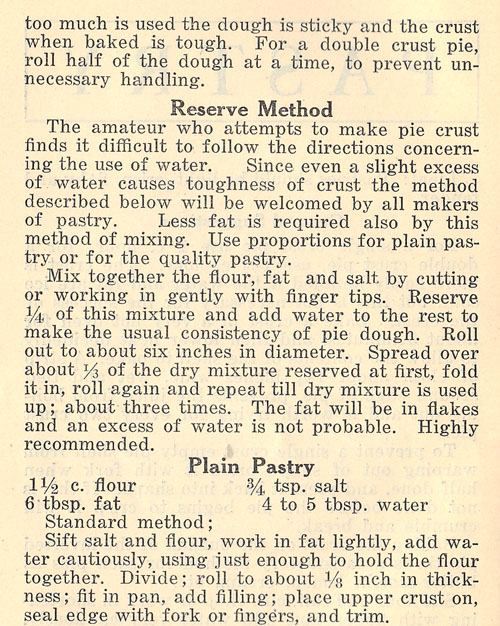

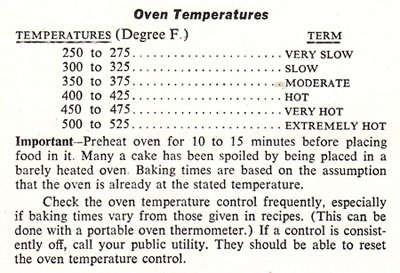

The first recipe in the booklet is for pie crust, below. These directions represent the style of writing throughout the booklet. I’ll let you read it and judge for yourself. (This is from the era before mixers, food processors, or even pastry cutters.) Note the directions for oven temperatures: “bake in a very hot oven for about 3 minutes, and then lower the heat decidedly”. Here is how to intrepret older oven temperature descriptions to degrees Fahrenheit.

Note that besides the instruction “hot oven for 3 minutes”, no time is given for baking the crust. This is true throughout this 1921 cookbook. The baking recipes just say “cook until done”. Some of the recipes for steamed puddings have a designated cooking time, but the desserts cooked on the stove top do not.

Note that besides the instruction “hot oven for 3 minutes”, no time is given for baking the crust. This is true throughout this 1921 cookbook. The baking recipes just say “cook until done”. Some of the recipes for steamed puddings have a designated cooking time, but the desserts cooked on the stove top do not.

Pie recipes include: lemon chiffon, berry, southern tomato, rhubarb, raisin, custard, mock mincemeat, cottage cheese, banana cream, and more. Tarts can be adapted from any of the pie recipes.

Puddings are thickened with cornstarch, tapioca, and flour. Cereal desserts are made from rice, cornmeal, bread and cracker crumbs. There are custards, fruits (raw and stewed and baked), and rose apples using red clove candies. Fruits include cranberries, oranges, apples, bananas, berries, grapes, figs, melons, pineapple, peaches, prunes. Gelatine desserts are based on plain gelatin (not jello). Baked puddings include dumplings, cobblers, and roly poly. Steamed puddings include carrot, cherry cup, chocolate, fruit, gingerbread, Hazzard Delicious (butter, sugar, nuts, flour, baking powder, milk, eggs), persimmon, plum, and suet. There are rosettes, timbales and fritters. Frozen desserts include fruit ices: ice cream from milk, cream, sugar and eggs, simply frozen, not churned, with variations including chocolate, orange, pinneapple, caramel, coffee, fig, tutti frutti, grape nut, maple, peppermint, and ginger. Mousses (a standard recipe with suggestions for flavoring) and parfaits (frozen desserts made with eggs, syrup) are included. The last section is sauces for puddings (cooked without eggs, cooked with eggs, uncooked with eggs), and sauces for ice cream.

Very few recipes in this booklet include chocolate!

I decide to make Tapioca Cream for this blog. Our grandson will join us for dinner and I think this is a fairly nutritous dessert because it includes milk and eggs, is relatively low in sugar, and has no added fat.

Tapioca is a starch made from cassava root. In the US, it is mainly used as a thickener, but in triopical areas of Africa and Asia, cassava is a staple food. Cassava is low in nutrition: it has no protein or fiber, is low in calories (important in areas of the world where food energy is a plus), and has insignificant amounts of viatmins and minerals. In the US, tapioca is sold as “minute tapioca” (and has been sold that way since at least 1921). I’ve also tried pearl tapioca – big round lumps of tapioca.

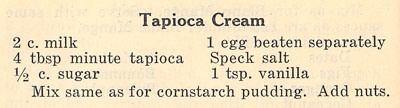

Here is the Tapioca Cream recipe from page 26:

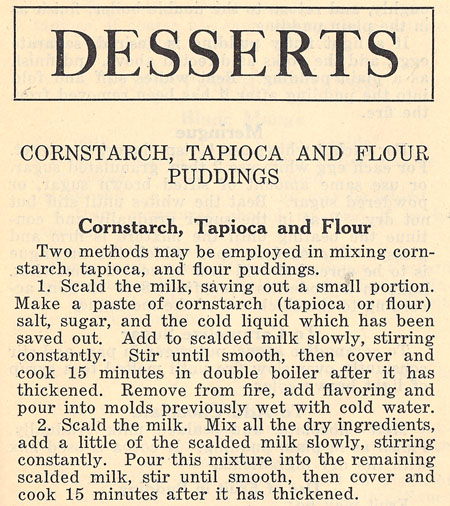

As you see, the mixing and cooking instructions are not given in the Tapioca Cream recipe. It says: “mix same as for cornstarch pudding”. Those instructions are six pages previous – page 19:

I learned that you do not have to scald milk from my book Kitchen Science. Therefore, I will simply mix together the tapioca, sugar, salt, and milk. Shall I use a double boilier to heat this mixture? I suspect that in 1921, you needed to cook in a double boiler to control the stove top temperature – note that the recipe says “remove from fire”. “Fire” sounds harder to control than today’s stove top burners! So I won’t use that step, but simply cook it in a saucepan on the stove top. Also, I will beat the egg whites with 3 tablespoons sugar, according to the instructions on my current package of minute tapioca. The modern recipe calls for 2 tablespoons less sugar and leaves out the nuts.

Tapioca Cream Pudding

serves 3-6

- 1/4 cup minute tapioca

- 6 tablespoons sugar, divided

- dash of salt

- 2 cups milk

- 1 egg yolk

- 1 egg white

- 1 teaspoon vanilla

Combine the tapioca, sugar, and salt in a cool pan, then add the milk and egg yolk. Let stand 5 minutes.

Heat the mixture to a full boil on medium heat, stirring constantly, then remove from heat. Let stand 20 minutes to cool.

Beat the egg white on high speed until soft peaks form. Gradually beat in 3 tablespoons sugar until stiff peaks form.

Fold the egg white mixture into the tapioca-milk mixture. Fold in the vanilla.

You can divide the pudding into single servings or not; you can serve warm or chilled.

I made only three custard cups, and it served three people! It was so good – I hadn’t made it in years and it’s a comfort food to me. I put some sliced strawberries on top and served it with cookies. My grandson liked to dip those cookies in the pudding!

I made only three custard cups, and it served three people! It was so good – I hadn’t made it in years and it’s a comfort food to me. I put some sliced strawberries on top and served it with cookies. My grandson liked to dip those cookies in the pudding!

Note: I used 3 tablespoons tapioca, as it stated on the package. But I would have liked it a little thicker, so I’d suggest the 4 tablespoons tapioca as written in Pastries and Desserts.

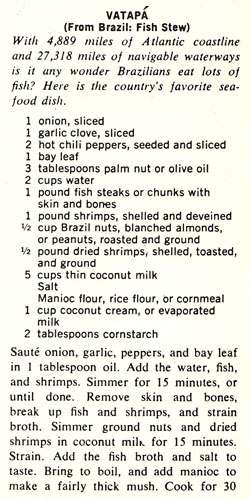

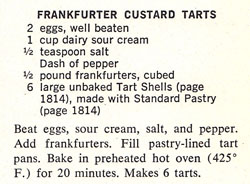

Sour Cream in its simplest form is “unpasteurized heavy sweet cream that has been allowed to stand in a warm place until it has become sour”. Commercial sour cream is made from “sweet cream chemically treated with lactic-acid bacteria to produce a thick cream with a mild tangy flavor”. The South American Cook Book begins with an interesting essay by Jean Gormaz on the widely varied cooking of this continent of many climates. Vatapa, a fish stew from Brazil, illustrates the variety of ingredients in South American cookery.

Sour Cream in its simplest form is “unpasteurized heavy sweet cream that has been allowed to stand in a warm place until it has become sour”. Commercial sour cream is made from “sweet cream chemically treated with lactic-acid bacteria to produce a thick cream with a mild tangy flavor”. The South American Cook Book begins with an interesting essay by Jean Gormaz on the widely varied cooking of this continent of many climates. Vatapa, a fish stew from Brazil, illustrates the variety of ingredients in South American cookery.

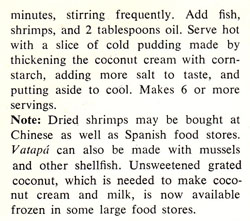

Cook books called Southeast Asian Cookery, Southern Cookery, and Southwest Cookery follow each other with no short entries between. (This volume of the Encyclopedia of Cookery sure has a lot of cook books in it.) The Southwestern cook book includes few dishes familiar to me, except chili sauce, tacos, and sopapillas. Carne Adobada is an example of a recipe I have never heard of before, and it takes days to make.

Cook books called Southeast Asian Cookery, Southern Cookery, and Southwest Cookery follow each other with no short entries between. (This volume of the Encyclopedia of Cookery sure has a lot of cook books in it.) The Southwestern cook book includes few dishes familiar to me, except chili sauce, tacos, and sopapillas. Carne Adobada is an example of a recipe I have never heard of before, and it takes days to make.

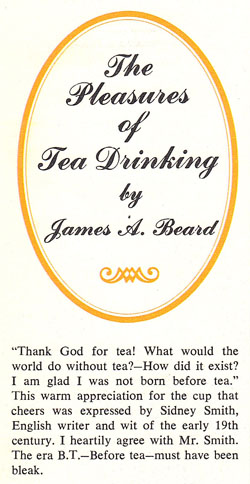

I would never make these, they do not sound tasty to me. And “taste” is an entry: “one of the senses of man”. Tea is honored with an essay by James Beard on “the pleasures of tea drinking”, and I like his era “B. T.” – before tea:

I would never make these, they do not sound tasty to me. And “taste” is an entry: “one of the senses of man”. Tea is honored with an essay by James Beard on “the pleasures of tea drinking”, and I like his era “B. T.” – before tea: Tetrazzini is a dish I discussed in

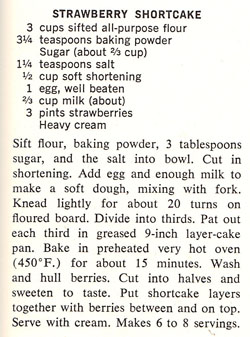

Tetrazzini is a dish I discussed in  Why did I choose this recipe? I have been making strawberry shortcake for years. But I have always started with my mother’s basic biscuit recipe, and just added “a bit” of sugar. This is an actual “shortcake” recipe. Plus, I like the way the dough is rolled out into a big circle and baked in a cake pan. Saves a step in cutting out the biscuits. And finally, I had some strawberries in the refrigerator looking to be used!

Why did I choose this recipe? I have been making strawberry shortcake for years. But I have always started with my mother’s basic biscuit recipe, and just added “a bit” of sugar. This is an actual “shortcake” recipe. Plus, I like the way the dough is rolled out into a big circle and baked in a cake pan. Saves a step in cutting out the biscuits. And finally, I had some strawberries in the refrigerator looking to be used! Meanwhile, slice the strawberries and add a tablespoon or so of sugar. Stir and allow to macerate until you serve the shortcake.

Meanwhile, slice the strawberries and add a tablespoon or so of sugar. Stir and allow to macerate until you serve the shortcake. This was excellent! I like the egg in the dough, and I like rolling it into one circle instead of biscuits. My dining partner said “yum, but not enough!” I take that as a thumbs up.

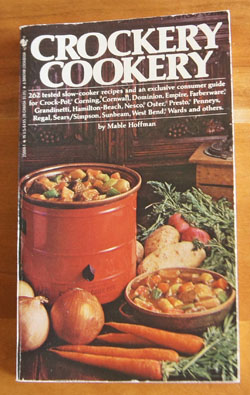

This was excellent! I like the egg in the dough, and I like rolling it into one circle instead of biscuits. My dining partner said “yum, but not enough!” I take that as a thumbs up. I just now realized: This paperback book has the same title and cover photo and publication date as my hardcover book

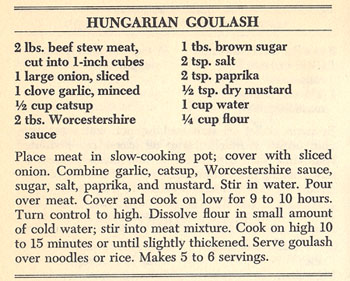

I just now realized: This paperback book has the same title and cover photo and publication date as my hardcover book  The recipe calls for beef stew meat, but I have a quantity of pork loin in the freezer so I decide to use that instead of beef.

The recipe calls for beef stew meat, but I have a quantity of pork loin in the freezer so I decide to use that instead of beef. This was very good. I’d make it again!

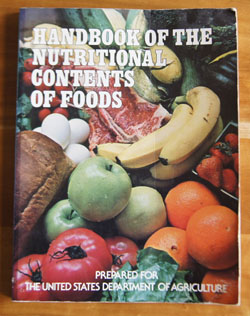

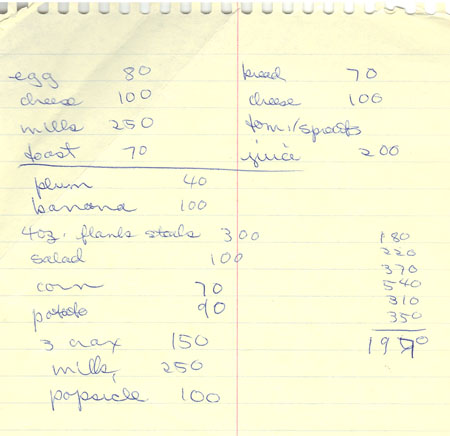

This was very good. I’d make it again! I bought the Handbook of the Nutritional Contents of Foods for myself new or used, I think sometime in the eighties. Around that time, I was developing a basic “eating plan” for myself, or maybe I should say “dieting plan”. You see, for years, I would diet strictly for months, eat sensibly for a short time, overindulge for weeks, then repeat the cycle. I drew up my first plan based on a diet given to me in the early seventies, before I left California. Later,

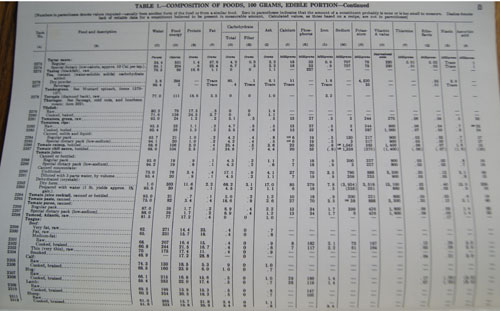

I bought the Handbook of the Nutritional Contents of Foods for myself new or used, I think sometime in the eighties. Around that time, I was developing a basic “eating plan” for myself, or maybe I should say “dieting plan”. You see, for years, I would diet strictly for months, eat sensibly for a short time, overindulge for weeks, then repeat the cycle. I drew up my first plan based on a diet given to me in the early seventies, before I left California. Later,  One thing I recall about looking up calories in this book is that it was difficult to find the calories in meats. I think maybe it was because I didn’t have a kitchen scale at the time, and would have to estimate the calories from the meat package label, using the amount sold (raw) and estimating the size of the portion I cut for myself.

One thing I recall about looking up calories in this book is that it was difficult to find the calories in meats. I think maybe it was because I didn’t have a kitchen scale at the time, and would have to estimate the calories from the meat package label, using the amount sold (raw) and estimating the size of the portion I cut for myself.

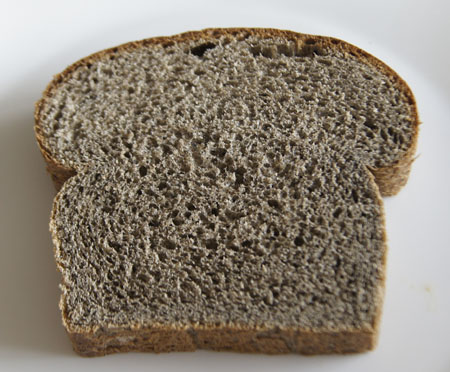

And it baked into a beautiful loaf. Here is a slice, showing the blue hue and the great texture:

And it baked into a beautiful loaf. Here is a slice, showing the blue hue and the great texture: I sniffed the loaf like I always do. Pee-yoo, it stinks! Something about the smell really turns me away. I ate a big bite and it tasted like it smelled. Yuck.

I sniffed the loaf like I always do. Pee-yoo, it stinks! Something about the smell really turns me away. I ate a big bite and it tasted like it smelled. Yuck.