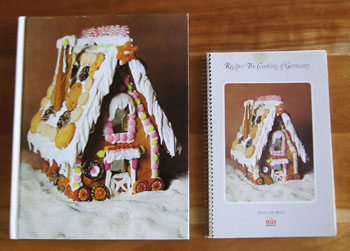

Cookbook #222: Cooking of Germany, Nika Standen Hazelton and the Editors of Time-Life Books, Time-Life Books, NY, 1969. Foods of the World series; revised 1973, reprinted 1974.

This is the fifth and last book that I own in the Foods of the World series. Once again, I look forward to discovering another interesting author as I open Cooking of Germany, just as I discovered M. F. K. Fisher in the Cooking of Provinvial France, Emily Hahn in the Cooking of China, Joseph Wechsberg in Cooking of Vienna’s Empire, and Rafael Steinberg in the Cooking of Japan.

This is the fifth and last book that I own in the Foods of the World series. Once again, I look forward to discovering another interesting author as I open Cooking of Germany, just as I discovered M. F. K. Fisher in the Cooking of Provinvial France, Emily Hahn in the Cooking of China, Joseph Wechsberg in Cooking of Vienna’s Empire, and Rafael Steinberg in the Cooking of Japan.

Nika Standen Hazelton is the author, and who is she? Let’s see what I can find. She was born in 1908, in Rome; her father was a German diplomat. She studied at the London School of Economics and began a career as a European journalist at the young age of 22, in 1930. In 1940, she emigrated to the US with her husband.

In the States, she started writing cookbooks. Her obituary states she authored 30 cookbooks, and also “was a frequent contributer to the major food magazines and for several decades wrote a column about food, wine and travel for The National Review“. Her writing style wove memoirs into her recipes, and several of her books remain cookbook standards. Her attitude towards cooking is described as “no-nonsense”. “Searching for Nika Hazelton, the no-nonsense cook” is a delightful 2011 blog entry by Sandra Lee. I chuckled several times at Sandra’s descriptions of this apparently full-of-attitude author.

So I am a bit abashed that I was ignorant of Nika Hazelton’s writing. She belongs among the other important woman authors of food articles and books in the twentieth century, alongside M. F. K. Fisher and Emily Hahn. (And why did I not read and appreciate these female authors of the Foods of the World series when I first received the books in the mail? I have no good answer.)

Nika Hazelton begins the introduction with “when I began to think about this book, I was puzzled . . . should the book be aboutt he cooking of present-day Germany? Should it be about the cooking I grew up with between World Wars I and II? . . . each approach could be illuminating, and each had its drawbacks.” Here is the paragraph that follows these thoughts – note her philosophical tone:

Her musings continue. “Why write about a bygone age? The Germany of those days is gone forever – and good riddance to it.”

This paragraph describes her decision for the book’s focus:

![]()

And:

“As in any cookbook, some readers will miss their own favorites, or question ingredients or techniques that went into making a typical dish. I can only remind them that no book is all-inclusive, and that most traditional dishes of any country come in almost as many versions as there are cooks. This is an asset rather than a fault, for it gives room for pleasant speculation on the whys and wherefores of a dish – pleasant speculation, because food and cooking are pleasant and comforting in themselves.”

“Food and cooking are pleasant and comforting in themselves.” A woman after my own heart.

The introduction is followed by the first chapter: “Surprises of the German Table”. Nika Hazelton writes that the tourist (of the late 1960s) might expect to find a Germany filled with the music of Bach and Beethoven, castles perched high above the Rhine, and Hansel-and-Gretel towns nestled in dark forests. Meals would be a long succession of sausages and sauerkraut followed by sauerbraten and dumplings served with great steins of beer “hoisted by hefty maidens”. But in reality, the tourist would fly in jets over the Rhine castles, and “The Gretels are miniskirted, the Hansels long-haired, and they sway to rock ‘n’ roll in the automobile-choked streets of their age-old towns.” Those automobiles would be Volkswagens. The tourist would find all the expected dishes, but they will be different in flavor and in an incredible variety of forms. And food is sold in “supermoden supermarkets”, offering foods “premixed, freeze-dried, precooked, and, of course, temptingly packaged for impulse buying, along with fresh foods from the world over.”

Here she describes why she thinks Americans are so comfortable with German food:

This book has wonderful full-page photographs. The photographer was German-born Ralph Crane, who worked for the NY Times as well as Time-Life books. Here is an example of the full-page photos in this book:

This book has wonderful full-page photographs. The photographer was German-born Ralph Crane, who worked for the NY Times as well as Time-Life books. Here is an example of the full-page photos in this book:

The second chapter is “How to Eat Five meals a Day”. I turn to a photo of a man in suit and tie, his wife in dark sweater and trousers. They sit at a table, under an elegant chandelier, complete with candles, flowers, and fancy dishware. She is feeding a bite of her food to the family dachshund. The photo caption tells us they are “dining informally at home”. Oh yes. Informal. (You should see my informal.)

The five-meals-a-day chapter exemplifies Nika Hazelton’s character as she describes not only the food, but the people and the traditions of German cooking. She takes us through a day in the life of a German in the mid-twentieth century, weaving the hours with people coming together and enjoying food, and compares the experiences of Germans today with those of yesteryears.

This paragraph exemplifies the chapter’s tone:

She mentions the grape harvest:

“Incidentally, for those who think that grape harvesting is romantic, with maidens in dirndls wearing Bacchic wreaths in their hair, I have news. Grape pickers wear jeans, sweaters and high rubber boots. The pretty dresses and stupendous beehive hairdos come later, at the Winzerfeste, or local vintners’ fêtes, where the merriment is astonishing indeed.”

At the end of the second (and each) chapter are recipes. Katerfisch, or “Fish for a Hangover” with tomato sauce and pickles, and Röllmopse, or “Rollmops”, are herring rolls filled with onion and pickle, “prized as a pick-me-up on a morning after”. Ah, those Germans.

Chapter 3 is “The Pleasures of Eating Out”. Here is an example:

Chapter 4 is “Old and New Ways of Party Giving”. Again, an example:

Nika Hazelton ties her own past with her own present:

The flavor and of the Cooking of Germany continues to the end of the book. The next chapters are “A Cooking History 2,000 Years Old”, “The Northern Style: Cold-Climate Cuisine”, “The Central Style: Rich and Filling”, “The Southern Style: A lighter Touch”, “Baking Raised to a Fine Art”, and “Festive Revelry and Nostalgic Holidays”. Here are a few thoughts about these chapters.

The flavor and of the Cooking of Germany continues to the end of the book. The next chapters are “A Cooking History 2,000 Years Old”, “The Northern Style: Cold-Climate Cuisine”, “The Central Style: Rich and Filling”, “The Southern Style: A lighter Touch”, “Baking Raised to a Fine Art”, and “Festive Revelry and Nostalgic Holidays”. Here are a few thoughts about these chapters.

- There is a great photo of a potato on page 134. I learn that potatoes are a new world vegetable, and of all the Europeans, Germans were the last import them. Today, potatoes are called “The King” of German vegetables and are used for Schnaps (an alcoholic beverage), dessert dumplings, hot potato salad, potato pancakes, potato soup, and potato dumplings, among other dishes.

- One of my favorite pages is the photo on page 154 of 26 different kinds of German wursts (sausages). “Everybody rejoices when November kills its pig” is the title of a photo caption.

- I enjoy the “Baking Raised to a Fine Art” chapter. Wonderful photos of German yeast breads. Photos of desserts, fancy and rich, like the gingerbread house on the cover of the book.

Need to mention

I find the recipe instructions in the hard cover and in the accompanying spiral bound booklet very well written. The “late Michael Field suprervised the adapting and writing of recipes for this book. One of America’s foremost food experts and culinary teachers, he wrote many articles for leading magazines.”

Another of the team that put together the Cooking of Germany is the consultant:

As you can see, the consultant was Irma Rhode. Born in 1900, she earned PhD in chemistry. I can imagine that she was the only female in her classes. Heck, I was one of the few women taking chemistry in the 1960s!

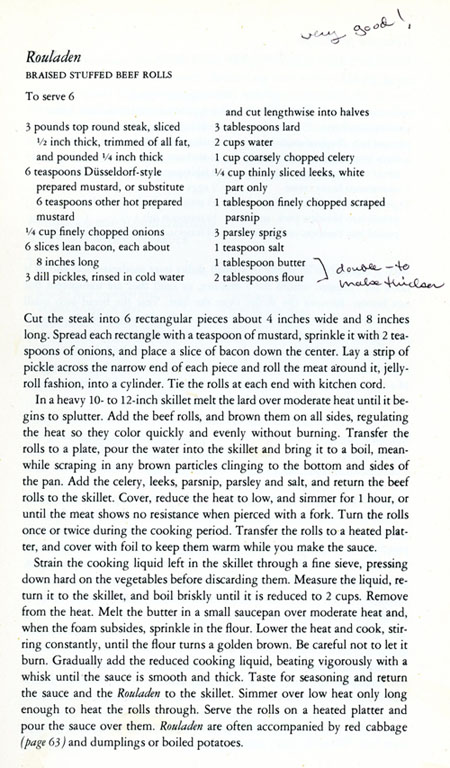

Rouladen for dinner

Time to get cooking! I pick up the spiral-bound book of recipes that accompanies the hardcover. I decide to make Rouladen for this blog. These are beef rolls, and the recipe suggests to serve them with spatzle (see scan below)). I’ve made Rouladen before but wow, how long ago was that! We both remember this dish but can’t remember the last time I made it and I can’t figure out why I haven’t made it since.

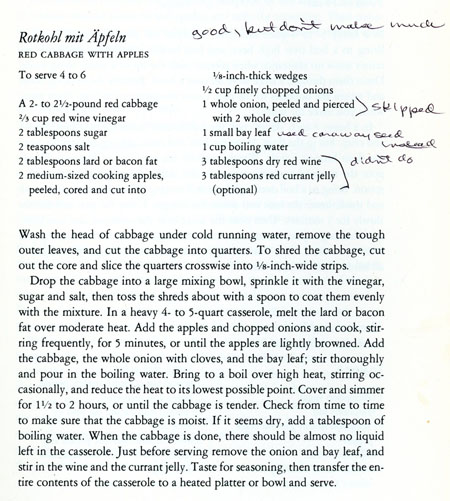

As suggested in the recipe, I’ll serve it with a little Red Cabbage with Apples.

As suggested in the recipe, I’ll serve it with a little Red Cabbage with Apples.

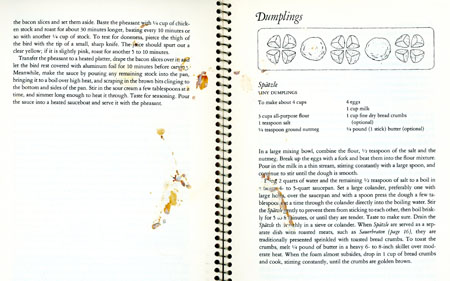

The rouladen recipe also suggests dumplings or spätzle, but I am going to cheat and use convenient potato dumplings, or gnocchi, sold these days in America as a shelf-stable pasta product. Below is the Cooking of Germany recipe for spätzle. You can see I used this recipe booklet, by the sticky pages at spätzle. I love spätzle! But they take a bit of time to make. (Someday I’ll make them again!)

I modified the rouladen recipe a bit: I increased the onions, leeks, and parsnip in the cooking liquid, and I added some pepper. I made the sauce a bit differently, as described in my version of the recipe, below.

Braised Stuffed Beef Rolls (Rouladen)

serves 2

- 1 pound thin sirloin (or top round) steak (my local market sells thin sirloin as “petite sirloin”)

- 2 teaspoons mustard (I used a brown mustard with seeds, but any type would work)

- 1/4 cup finely chopped onions

- 2 slices bacon, each about 8 inches long

- 1 whole dill pickle, cut lengthwise into halves

- 1 tablespoon lard (or use butter)

- 1/3 cup chopped celery

- 1/3 cup thinly sliced leeks, white part only

- 1/3 cup chopped parsnip (optional; or substitute a carrot)

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- pepper to taste

- 1 cup water

- 1 big sprig of parsley

- 1 tablespoon butter

- 2 tablespoons flour

Pound the steak until it is 1/4 inch thick. (I put it in a ziplock bag and pounded with a mallet.) If you are using a single piece of round steak or sirloin steak, cut it into two rectangular pieces about 4 inches wide and 8 inches long after pounding. I found that the petite sirloin steaks worked perfectly, as they were sold already the perfect size for this dish.

Spread each rectangle with a teaspoon of mustard, then sprinkle with 2 teaspoons of onions (save the remaining onions for later). Place a piece of bacon lengthwise down the center. Lay a dill pickle half across the narrow end of each piece and beginning at the pickle end, roll the meat around it, jelly-roll fashion, into a cylinder. Tie the rolls at each end with kitchen cord.

Choose a deep skillet with a heavy lid. I used my old cast-iron stewing pot; a LeCreuset or any heavy cooking pan or pot or skillet would work. Heat the skillet over moderate heat; add the lard (or butter) and heat until it begins to splutter. Add the beef rolls, and brown them on all sides, regulating the heat so they color quickly and evenly without burning. Transfer the rolls to a plate and set aside.

Choose a deep skillet with a heavy lid. I used my old cast-iron stewing pot; a LeCreuset or any heavy cooking pan or pot or skillet would work. Heat the skillet over moderate heat; add the lard (or butter) and heat until it begins to splutter. Add the beef rolls, and brown them on all sides, regulating the heat so they color quickly and evenly without burning. Transfer the rolls to a plate and set aside.

Add the celery, leeks, parsnip, remaining onion, and salt and pepper to the skillet and cook and stir a minute or two to soften the vegetables. Add the water and bring it to a boil, stirring and scraping in any brown particles clinging to the bottom and sides of the pan. Add the parsley. Turn the heat to low and cover the pot. Monitor the pot for awhile: you want a gentle simmer. Let it simmer for an hour or so, turning the rolls once or twice.

Remove the rolls from the pot and cover with foil to keep them from drying out while you make the sauce.

Let the sauce cool awhile in the pot, then scoop the vegetables from the pot with a slotted spoon. Pour the liquid into a gravy separator. Alternatively, if your gravy separator has a strainer-type top, pour the entire contents of the pot through the strainer into the separator. You want these cooked vegetables! Save them!

When the fat has separated from the water layer, pour the water layer into a blender or food processor, or better yet, into the cylindric container that comes with an immersion blender. Add the saved cooked veggies to the liquid, and blend or process or use an immersion blender to homogenize the mixture.

Meanwhile, melt the tablespoon of butter in the skillet until it is foaming, then slowly add the 2 tablespoons of flour, stirring constantly. When all the flour is incorporated, stir a minute or two more, but do not let it burn. Then, slowly and with constant stirring, add the blended broth-vegetable mixture. When it is nicely thickened and bubbly, add the beef rolls, cover the pot, and heat 5-10 minutes to get the rolls to serving temperature.

These were delicious! The gravy was amazing, thick and full of flavor. The pickle inside was fun. These remind us of one of our favorite meals, called “little piggies” by my husband’s family. It’s still about his favorite meal – strips of bacon on strips of round steak, rolled and secured with a toothpick, cooked in a skillet and served over mashed potatoes with gravy. I like the rouladen as made above with tender sirloin steak, because there is less fuss in preparation, and the de-fatted gravy isn’t greasy.

These were delicious! The gravy was amazing, thick and full of flavor. The pickle inside was fun. These remind us of one of our favorite meals, called “little piggies” by my husband’s family. It’s still about his favorite meal – strips of bacon on strips of round steak, rolled and secured with a toothpick, cooked in a skillet and served over mashed potatoes with gravy. I like the rouladen as made above with tender sirloin steak, because there is less fuss in preparation, and the de-fatted gravy isn’t greasy.

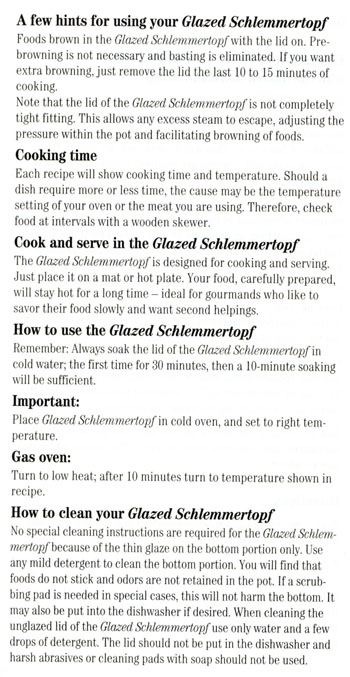

A “Schlemmertopf” is a covered clay baking pot. I wrote a lot of material on clay pots in

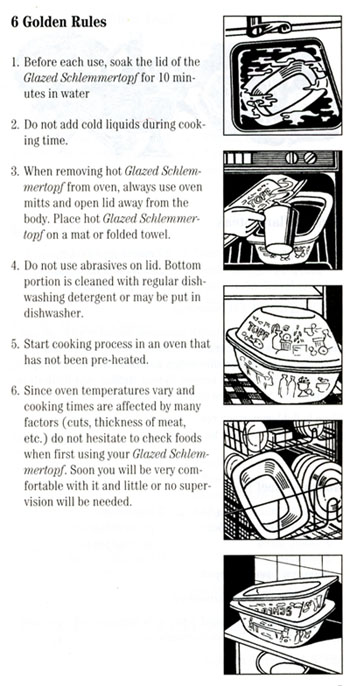

A “Schlemmertopf” is a covered clay baking pot. I wrote a lot of material on clay pots in  And Six Golden Rules:

And Six Golden Rules: The first 23 pages of this booklet is written in English, then (as far as I can tell) the same instructions and recipes are written in Spanish and then in French. Example recipes are stuffed flank steak, beef stew, meat loaf, beef cabbage rolls, roast beef, chicken shanghai (I made this for

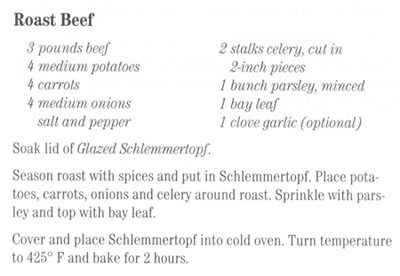

The first 23 pages of this booklet is written in English, then (as far as I can tell) the same instructions and recipes are written in Spanish and then in French. Example recipes are stuffed flank steak, beef stew, meat loaf, beef cabbage rolls, roast beef, chicken shanghai (I made this for  My roast is only about a pound and a half, so I will cut the recipe in half. Note how the recipe (above) does not state what cut of beef to use, nor does it tell me if the potatoes, carrots, and onions are to be peeled or chopped. It does direct the cook to cut the celery in “2-inch pieces”. I decided to peel and cut in half the potatoes, carrrots, and onions.

My roast is only about a pound and a half, so I will cut the recipe in half. Note how the recipe (above) does not state what cut of beef to use, nor does it tell me if the potatoes, carrots, and onions are to be peeled or chopped. It does direct the cook to cut the celery in “2-inch pieces”. I decided to peel and cut in half the potatoes, carrrots, and onions.

This was good. The potatoes were nicely browned and not mushy inside. I liked the onions too – browned and soft and perfect. I wasn’t able to make a gravy, so I served it with ketchup. (I liked the

This was good. The potatoes were nicely browned and not mushy inside. I liked the onions too – browned and soft and perfect. I wasn’t able to make a gravy, so I served it with ketchup. (I liked the  This treasure is my mother’s copy of my book of the same name, as covered in my

This treasure is my mother’s copy of my book of the same name, as covered in my

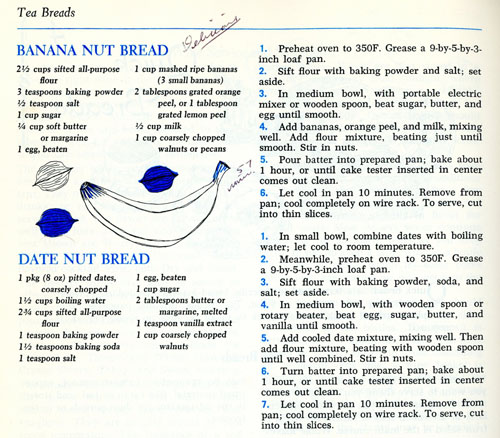

I have about 3 or 4 banana bread recipes – I rotate through different versions, but most of my recipes call for vegetable oil – this one uses butter or margarine instead. Might be interesting to try. Seems I often have ripe bananas to use up!

I have about 3 or 4 banana bread recipes – I rotate through different versions, but most of my recipes call for vegetable oil – this one uses butter or margarine instead. Might be interesting to try. Seems I often have ripe bananas to use up!

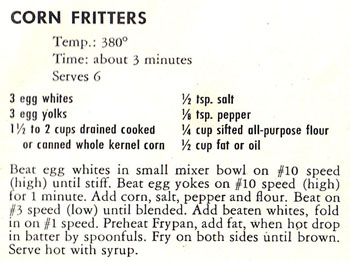

On the recipe Chili Con Carne in Red Wine, she commented it was “Pretty good, kinda runny”. I think she served it with the suggested Polenta Squares, a recipe later in the book, because she commented at the polenta squares “Good – I like it”. This makes me chuckle. I too like tomato-based sauces over polenta. I just discovered home-cooked polenta a few years ago. My dining partner sort of likes it, and I can imagine my father felt the same way. So her “Good – I like it” is a sort of rebellion. (I had no idea she ever tried a polenta dish.) She liked the deep fried Corn Fritters, but thought the Chili Con Carne only “fair”.

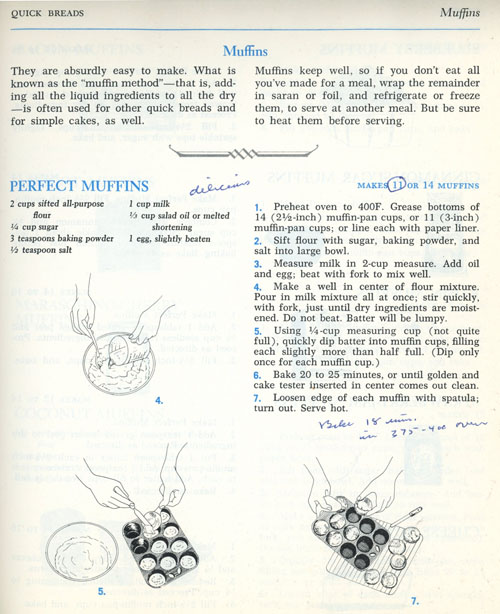

On the recipe Chili Con Carne in Red Wine, she commented it was “Pretty good, kinda runny”. I think she served it with the suggested Polenta Squares, a recipe later in the book, because she commented at the polenta squares “Good – I like it”. This makes me chuckle. I too like tomato-based sauces over polenta. I just discovered home-cooked polenta a few years ago. My dining partner sort of likes it, and I can imagine my father felt the same way. So her “Good – I like it” is a sort of rebellion. (I had no idea she ever tried a polenta dish.) She liked the deep fried Corn Fritters, but thought the Chili Con Carne only “fair”. These muffins are cake-like, or cupcake-like. The muffins I make are usually packed with bananas or apples or carrots, or whole grains, so to us, they tasted “less-healthy-than-usual”. Although, after my first bite of one of these muffins, I just wanted . . . more!

These muffins are cake-like, or cupcake-like. The muffins I make are usually packed with bananas or apples or carrots, or whole grains, so to us, they tasted “less-healthy-than-usual”. Although, after my first bite of one of these muffins, I just wanted . . . more! This might have belonged to my maternal grandmother. There is very little handwriting in it, but what there is looks like hers. Or it might have come from

This might have belonged to my maternal grandmother. There is very little handwriting in it, but what there is looks like hers. Or it might have come from

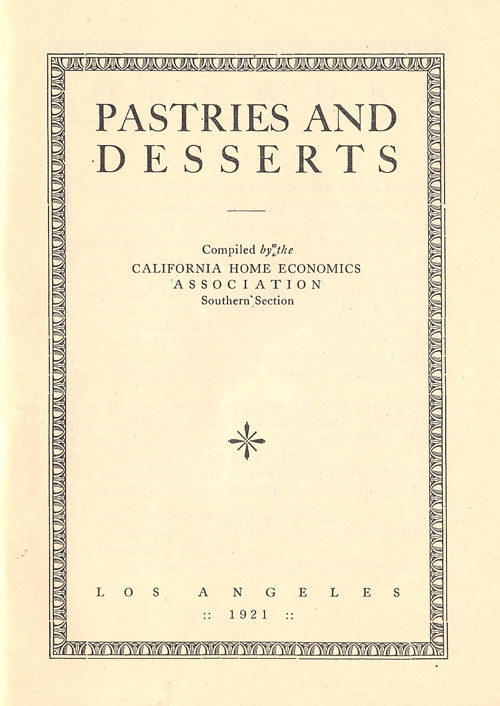

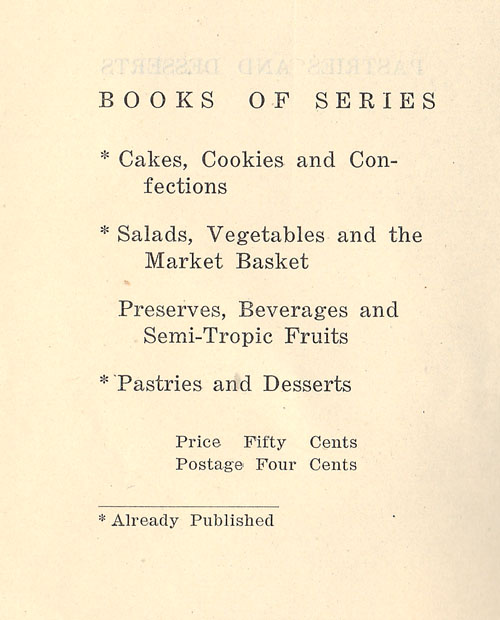

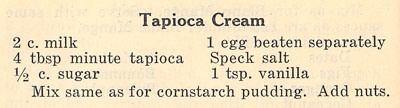

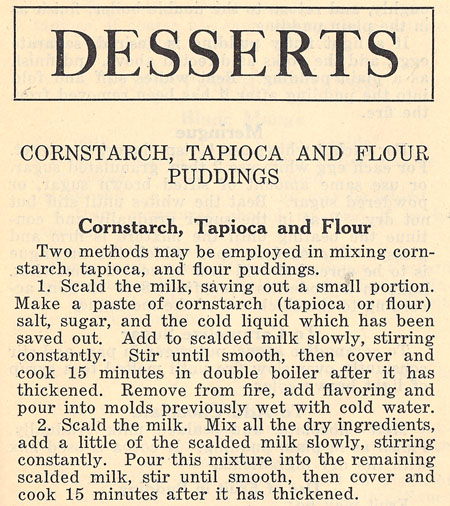

The entire content has a pleasing typeface and layout, no typos, is well-organized with cross-references, and has a very useful index at the end. The content is by the California Home Economics Association, Southern Section, but who is responsible for the printing of this 1921 cookbook? I find “Press of Clyde Browne” and “Cover Design by Stanley Edwards” on the back cover:

The entire content has a pleasing typeface and layout, no typos, is well-organized with cross-references, and has a very useful index at the end. The content is by the California Home Economics Association, Southern Section, but who is responsible for the printing of this 1921 cookbook? I find “Press of Clyde Browne” and “Cover Design by Stanley Edwards” on the back cover: Clyde Browne, was a self-identified printer, according to a

Clyde Browne, was a self-identified printer, according to a  This foreword tells us that the

This foreword tells us that the

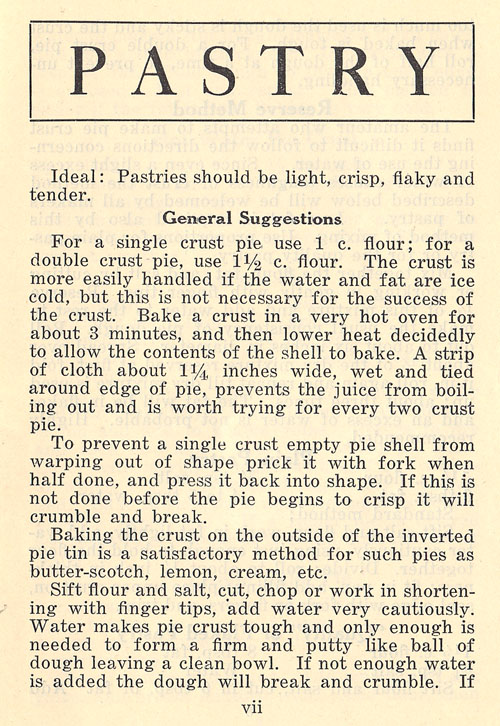

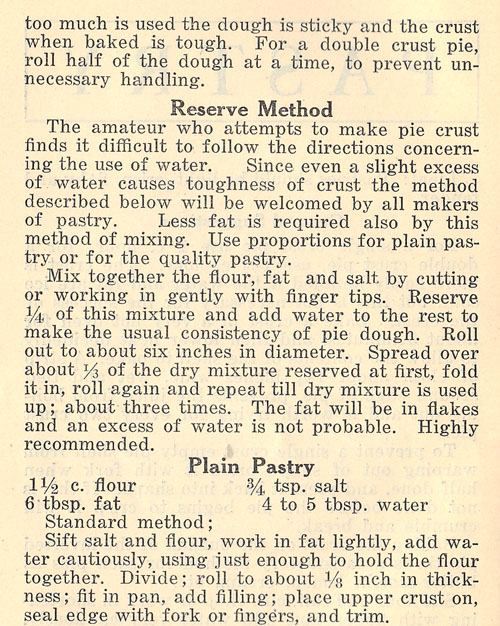

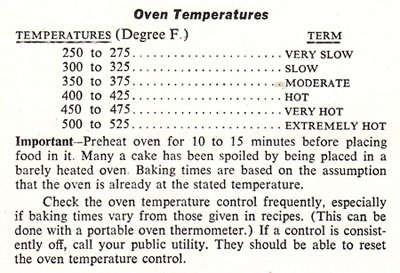

Note that besides the instruction “hot oven for 3 minutes”, no time is given for baking the crust. This is true throughout this 1921 cookbook. The baking recipes just say “cook until done”. Some of the recipes for steamed puddings have a designated cooking time, but the desserts cooked on the stove top do not.

Note that besides the instruction “hot oven for 3 minutes”, no time is given for baking the crust. This is true throughout this 1921 cookbook. The baking recipes just say “cook until done”. Some of the recipes for steamed puddings have a designated cooking time, but the desserts cooked on the stove top do not.

I made only three custard cups, and it served three people! It was so good – I hadn’t made it in years and it’s a comfort food to me. I put some sliced strawberries on top and served it with cookies. My grandson liked to dip those cookies in the pudding!

I made only three custard cups, and it served three people! It was so good – I hadn’t made it in years and it’s a comfort food to me. I put some sliced strawberries on top and served it with cookies. My grandson liked to dip those cookies in the pudding!

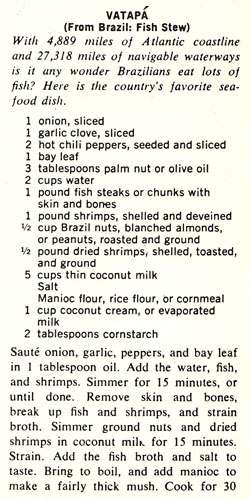

Sour Cream in its simplest form is “unpasteurized heavy sweet cream that has been allowed to stand in a warm place until it has become sour”. Commercial sour cream is made from “sweet cream chemically treated with lactic-acid bacteria to produce a thick cream with a mild tangy flavor”. The South American Cook Book begins with an interesting essay by Jean Gormaz on the widely varied cooking of this continent of many climates. Vatapa, a fish stew from Brazil, illustrates the variety of ingredients in South American cookery.

Sour Cream in its simplest form is “unpasteurized heavy sweet cream that has been allowed to stand in a warm place until it has become sour”. Commercial sour cream is made from “sweet cream chemically treated with lactic-acid bacteria to produce a thick cream with a mild tangy flavor”. The South American Cook Book begins with an interesting essay by Jean Gormaz on the widely varied cooking of this continent of many climates. Vatapa, a fish stew from Brazil, illustrates the variety of ingredients in South American cookery.

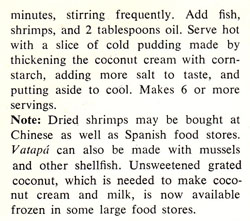

Cook books called Southeast Asian Cookery, Southern Cookery, and Southwest Cookery follow each other with no short entries between. (This volume of the Encyclopedia of Cookery sure has a lot of cook books in it.) The Southwestern cook book includes few dishes familiar to me, except chili sauce, tacos, and sopapillas. Carne Adobada is an example of a recipe I have never heard of before, and it takes days to make.

Cook books called Southeast Asian Cookery, Southern Cookery, and Southwest Cookery follow each other with no short entries between. (This volume of the Encyclopedia of Cookery sure has a lot of cook books in it.) The Southwestern cook book includes few dishes familiar to me, except chili sauce, tacos, and sopapillas. Carne Adobada is an example of a recipe I have never heard of before, and it takes days to make.

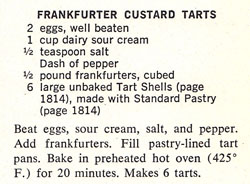

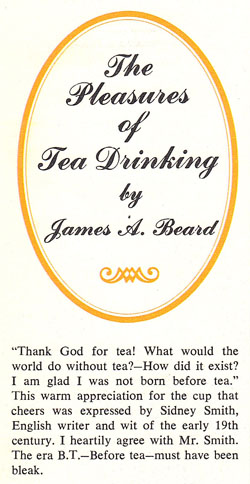

I would never make these, they do not sound tasty to me. And “taste” is an entry: “one of the senses of man”. Tea is honored with an essay by James Beard on “the pleasures of tea drinking”, and I like his era “B. T.” – before tea:

I would never make these, they do not sound tasty to me. And “taste” is an entry: “one of the senses of man”. Tea is honored with an essay by James Beard on “the pleasures of tea drinking”, and I like his era “B. T.” – before tea: Tetrazzini is a dish I discussed in

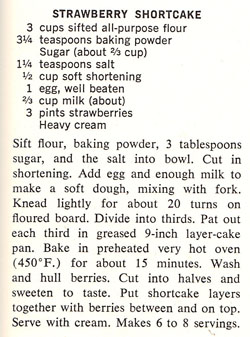

Tetrazzini is a dish I discussed in  Why did I choose this recipe? I have been making strawberry shortcake for years. But I have always started with my mother’s basic biscuit recipe, and just added “a bit” of sugar. This is an actual “shortcake” recipe. Plus, I like the way the dough is rolled out into a big circle and baked in a cake pan. Saves a step in cutting out the biscuits. And finally, I had some strawberries in the refrigerator looking to be used!

Why did I choose this recipe? I have been making strawberry shortcake for years. But I have always started with my mother’s basic biscuit recipe, and just added “a bit” of sugar. This is an actual “shortcake” recipe. Plus, I like the way the dough is rolled out into a big circle and baked in a cake pan. Saves a step in cutting out the biscuits. And finally, I had some strawberries in the refrigerator looking to be used! Meanwhile, slice the strawberries and add a tablespoon or so of sugar. Stir and allow to macerate until you serve the shortcake.

Meanwhile, slice the strawberries and add a tablespoon or so of sugar. Stir and allow to macerate until you serve the shortcake. This was excellent! I like the egg in the dough, and I like rolling it into one circle instead of biscuits. My dining partner said “yum, but not enough!” I take that as a thumbs up.

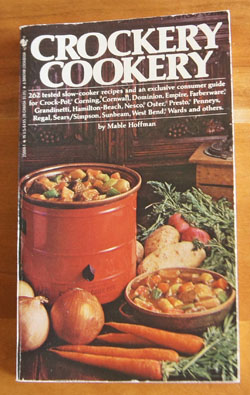

This was excellent! I like the egg in the dough, and I like rolling it into one circle instead of biscuits. My dining partner said “yum, but not enough!” I take that as a thumbs up. I just now realized: This paperback book has the same title and cover photo and publication date as my hardcover book

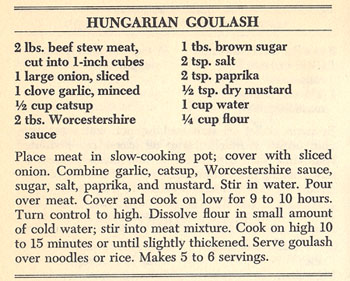

I just now realized: This paperback book has the same title and cover photo and publication date as my hardcover book  The recipe calls for beef stew meat, but I have a quantity of pork loin in the freezer so I decide to use that instead of beef.

The recipe calls for beef stew meat, but I have a quantity of pork loin in the freezer so I decide to use that instead of beef. This was very good. I’d make it again!

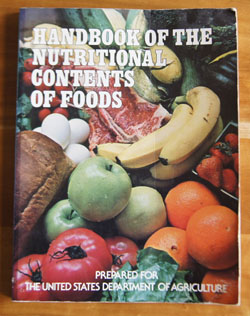

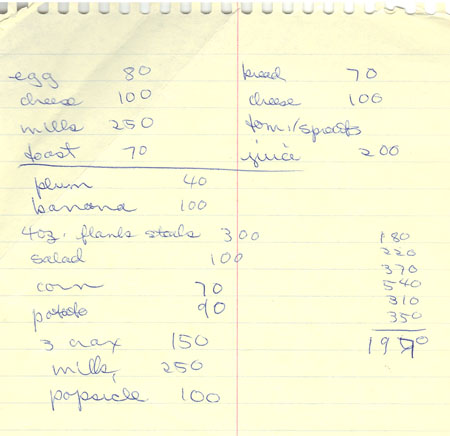

This was very good. I’d make it again! I bought the Handbook of the Nutritional Contents of Foods for myself new or used, I think sometime in the eighties. Around that time, I was developing a basic “eating plan” for myself, or maybe I should say “dieting plan”. You see, for years, I would diet strictly for months, eat sensibly for a short time, overindulge for weeks, then repeat the cycle. I drew up my first plan based on a diet given to me in the early seventies, before I left California. Later,

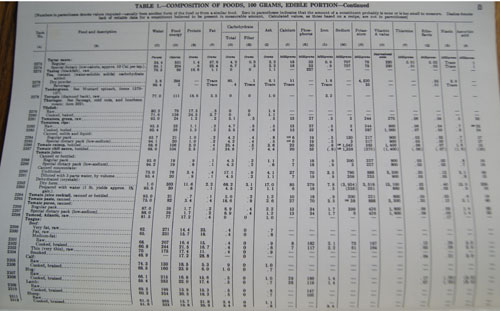

I bought the Handbook of the Nutritional Contents of Foods for myself new or used, I think sometime in the eighties. Around that time, I was developing a basic “eating plan” for myself, or maybe I should say “dieting plan”. You see, for years, I would diet strictly for months, eat sensibly for a short time, overindulge for weeks, then repeat the cycle. I drew up my first plan based on a diet given to me in the early seventies, before I left California. Later,  One thing I recall about looking up calories in this book is that it was difficult to find the calories in meats. I think maybe it was because I didn’t have a kitchen scale at the time, and would have to estimate the calories from the meat package label, using the amount sold (raw) and estimating the size of the portion I cut for myself.

One thing I recall about looking up calories in this book is that it was difficult to find the calories in meats. I think maybe it was because I didn’t have a kitchen scale at the time, and would have to estimate the calories from the meat package label, using the amount sold (raw) and estimating the size of the portion I cut for myself.

And it baked into a beautiful loaf. Here is a slice, showing the blue hue and the great texture:

And it baked into a beautiful loaf. Here is a slice, showing the blue hue and the great texture: I sniffed the loaf like I always do. Pee-yoo, it stinks! Something about the smell really turns me away. I ate a big bite and it tasted like it smelled. Yuck.

I sniffed the loaf like I always do. Pee-yoo, it stinks! Something about the smell really turns me away. I ate a big bite and it tasted like it smelled. Yuck. My Simac Pastamaker MX700 was a gift from my husband in 1998. I had been making my own pasta for years, using a Kitchenaid mixer to mix the dough, and a manual Marcato pasta maker to roll the dough and form the noodles (see my post, the

My Simac Pastamaker MX700 was a gift from my husband in 1998. I had been making my own pasta for years, using a Kitchenaid mixer to mix the dough, and a manual Marcato pasta maker to roll the dough and form the noodles (see my post, the  It’s a lot of fun! And time-consuming, yes. A decade or so ago I stored the Pastamaker down in the basement to make room for other things on my countertop. I don’t think I’ve used it since then. Now I have a great excuse to pull it back up, clean it, and make some great pasta. (I love retirement!)

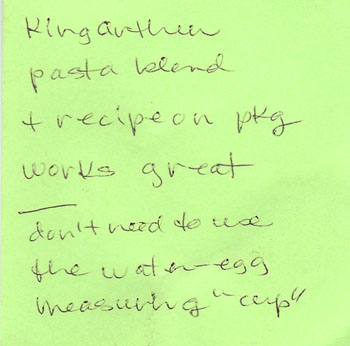

It’s a lot of fun! And time-consuming, yes. A decade or so ago I stored the Pastamaker down in the basement to make room for other things on my countertop. I don’t think I’ve used it since then. Now I have a great excuse to pull it back up, clean it, and make some great pasta. (I love retirement!) My note tells me that I used King Arthur Flour “pasta blend” the last time I made make the dough in the Simac. The reference to the water-egg measuring “cup” means that I used the package instructions for measuring the proper ratio of flour to egg-plus-water. The “cup” was shipped with Simac; it’s a specialized plastic measuring cup with levels marked for water and egg. BUT: these markings do not correlate with ounces, milliliters, or even cups. I never wrote down the exact capacity of that “measuring cup”. Each time I wanted to make pasta in the Simac, I had to locate this single-purpose utensil. I’m glad I wrote that note to myself! – now I know the proper ratio of wet to dry ingredients and can use a regular standard measuring cup.

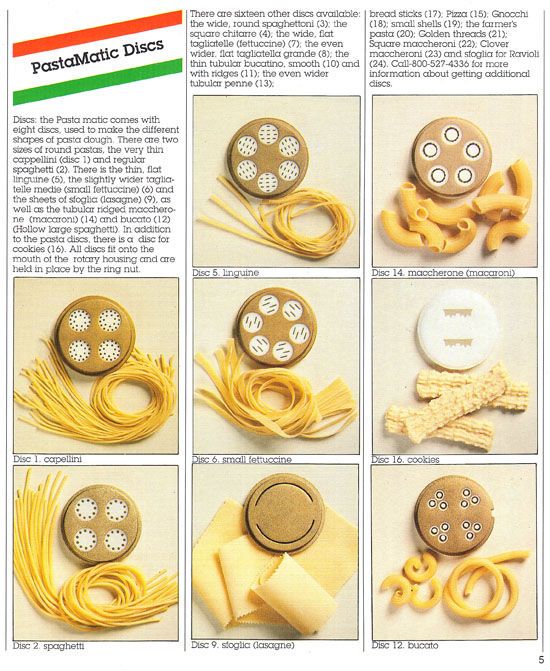

My note tells me that I used King Arthur Flour “pasta blend” the last time I made make the dough in the Simac. The reference to the water-egg measuring “cup” means that I used the package instructions for measuring the proper ratio of flour to egg-plus-water. The “cup” was shipped with Simac; it’s a specialized plastic measuring cup with levels marked for water and egg. BUT: these markings do not correlate with ounces, milliliters, or even cups. I never wrote down the exact capacity of that “measuring cup”. Each time I wanted to make pasta in the Simac, I had to locate this single-purpose utensil. I’m glad I wrote that note to myself! – now I know the proper ratio of wet to dry ingredients and can use a regular standard measuring cup. I carry the Pastamaker upstairs and find the dies (hidden in a pottery jar upstairs). Some of the dies are crusted with dried dough. Oh, I remember, it’s hard to get the dough out of the tiny slits and holes. Sometimes they clog during use, or the dough doesn’t feed properly through them. Hmmm. I better set aside an afternoon for my re-experiment with my Pastamaker.

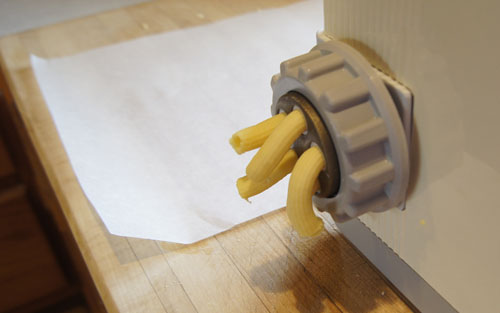

I carry the Pastamaker upstairs and find the dies (hidden in a pottery jar upstairs). Some of the dies are crusted with dried dough. Oh, I remember, it’s hard to get the dough out of the tiny slits and holes. Sometimes they clog during use, or the dough doesn’t feed properly through them. Hmmm. I better set aside an afternoon for my re-experiment with my Pastamaker. I decide to make macaroni, because I can make spaghetti and flat noodles any old time in my Marcato.

I decide to make macaroni, because I can make spaghetti and flat noodles any old time in my Marcato. Boil for 30 seconds and check for al dente; boil another 30 seconds if necessary. In Colorado, though, I cooked my macaroni for 3-4 minutes and it was perfect.

Boil for 30 seconds and check for al dente; boil another 30 seconds if necessary. In Colorado, though, I cooked my macaroni for 3-4 minutes and it was perfect.

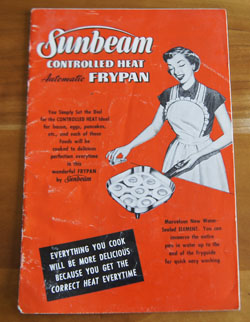

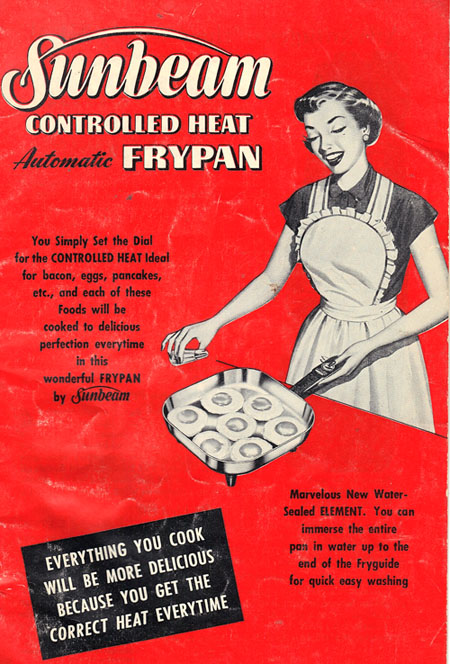

I discussed electric fry pans in

I discussed electric fry pans in

Look at all the Sunbeam appliances! Mixer (see my

Look at all the Sunbeam appliances! Mixer (see my

I liked these! But, my dining partner wasn’t impressed. The Southwestern Chicken was enough for him. I think these would have been good with syrup, as suggested in the recipe. I would like them fried in less oil than I used. This is a good recipe for very easy corn fritters; I just need to figure out how to include them in a dinner – or breakfast – plan.

I liked these! But, my dining partner wasn’t impressed. The Southwestern Chicken was enough for him. I think these would have been good with syrup, as suggested in the recipe. I would like them fried in less oil than I used. This is a good recipe for very easy corn fritters; I just need to figure out how to include them in a dinner – or breakfast – plan.